Thomas Doty – Storyteller

Ti'lomikh – Native Village

|

Welcome! Since I was a child I have been visiting the ancient Takelma village site of Ti'lomikh. And since 1981, when I began work as a native storyteller, I have been researching the lore and history of Ti'lomikh. This has been an adventure as well as a long and often challenging journey. Much of what is known is buried in reams of linguistic texts, unpublished field notes, back rooms of museums and in the memories of elders. And my own memories of conversations with relations who are no longer with us. The purpose of this project is to bring all of this information together on this web page. Enjoy!

The Ti'lomikh Project was funded by the Robert M. Stafrin Fund of the Oregon Community Foundation. To use this page, click on a title to show the text in that section. Click on the title again to hide it. Refresh the page to close all sections.

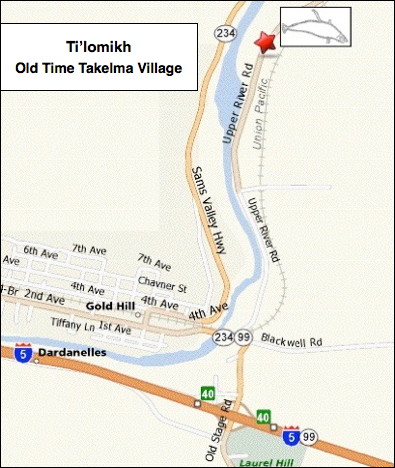

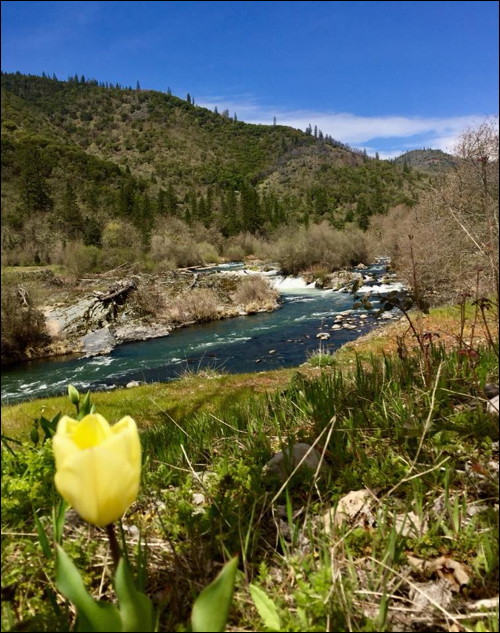

Near Gold Hill in southern Oregon, the Ti'lomikh village site stretches a mile from the red star to a hundred yards or so below the Highway 234/99 bridge (Blackwell Rd), on both sides of the Rogue River. |

|

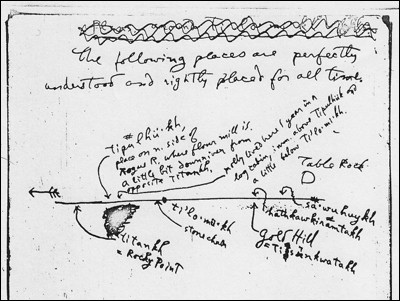

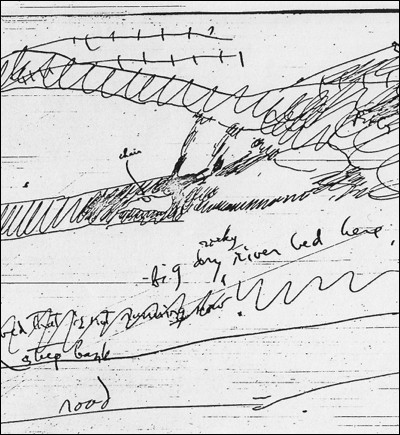

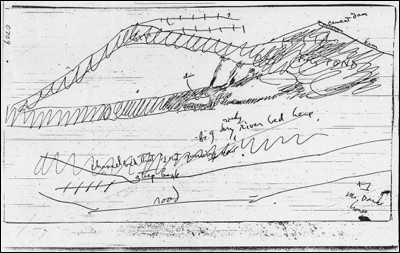

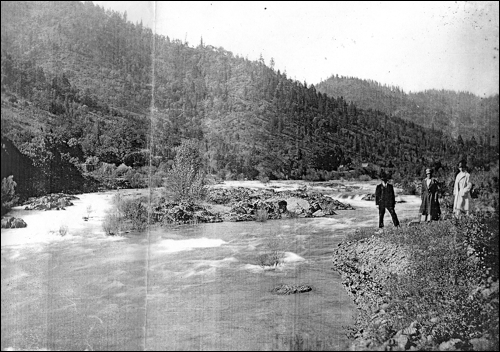

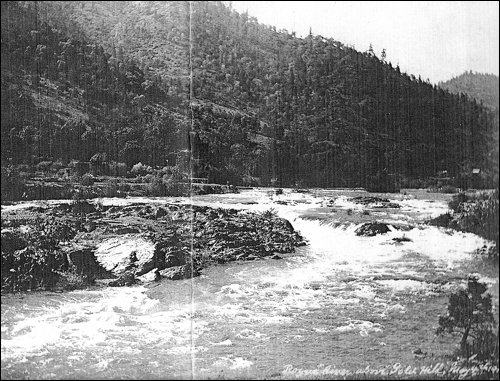

Ti'lomikh was a Takelma village located on both sides of the Rogue River near Gold Hill in southern Oregon. It was a large village, a mile from the main cemetery on the downriver end to the spring that was a source of good water on the upriver end. For thousands of years, Ti'lomikh was a thriving, well-populated village, and home of the annual Sacred Salmon Ceremony, the only one for miles around. With the arrival of Europeans in the early 1800s, followed by the Rogue River Indian Wars of the 1850s, and the five Trails of Tears in 1856, the village quickly became a ghost town, with only a few hardy folks staying on. They would disappear within a few years, and any sign of their houses, a few years after that. In 1933, linguist and anthropologist John Peabody Harrington brought Takelmas Frances Johnson and Molly Orton from the reservations in northern Oregon back to their Rogue Valley homeland. He made two trips, and they spent several days visiting native sites, including Ti'lomikh. Harrington's field notes from those trips, together with Edward Sapir's works on the Takelmas from his visits to Siletz in 1906, provided a wealth of linguistic and cultural information about the Takelmas, including Ti'lomikh. In 2007, Takelma elder Agnes Baker-Pilgrim, Keeper of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony, brought the ceremony from the nearby Applegate River where it had been happening for over a decade, back to its original location at Ti'lomikh. Hundreds of folks showed up! For the first time in over 150 years, Ti'lomikh was once again alive with native activities. The Takelma language is unique. It is its own language family, and not related to any other language in the world. It was spoken only by the Takelmas and their close relations the Cow Creeks who have made southern Oregon their home for thousands of years. Southern Oregon is rich in language diversity. To the east the Klamaths and Modocs speak Lutuamian, to the south and along the Klamath River, the Shastas and Karuks speak Hokan, and on the coast near the mouth of the Klamath, the Yuroks speak Algonquian. And then there are Athabascan speakers all over southern Oregon: the Tututni and Tolowa people on the coast, the Galice Creek and the Applegate Creek Indians along the Rogue and Applegate Rivers, and the Umpquas to the north. These are all distinct language families -- not just different dialects of the same language -- and they all occur within a 150 mile radius of the Takelma's Rogue Valley homeland. The different systems used by Edward Sapir and John Peabody Harrington in recording the Takelma language can make for some confusion. For instance, in Takelma there is a sound between a "D" and a "T" that is not made in English. When writing down the language, Sapir used a "D" system and Harrington a "T" system. So Sapir's name for the village is Dilomi and Harrington's is Ti'lomikh. Though they refer to the same place, some historians who didn't know this listed them as separate places. To slightly complicate the matter further, I have chosen to use both! And this is why. Some words have been in use for generations, and with these, I tend to go with what people are used to hearing. So the name of the people is Takelma, not Dagelma. However, the giant dragonfly in the myths is Daldal, not Taltal ... and so on.... When I am using a word that seems new to a contemporary ear, I tend to go with Harrington's system. But there's more! There is a similar sound issue for "G" and "K," (folks are used to hearing Frances Johnson's Indian name as Gwisgwashan, not Kwiskwashan) and, well, the language complications go on and on. Interestingly enough, Sapir and Harrington gathered the Takelma language from the same native speakers, but heard certain sounds differently. When it comes to translating Takelma words into English, I do this from the native point of view. Sapir translates the village name of Dilomi as "west of which are cedars," lom being the word for cedar. This is perfectly correct. However, I like to go a step further. To native people, all beings are people and very much alive, including the Cedar People. So from the Takelma point of view, I translate Ti'lomikh as "west of here live the Cedar People." This gives me the opportunity to bring a bit of native culture back into the language, even in English! Despite its remote home in southern Oregon, and its uniqueness in world languages, the Takelma language is fairly well known, especially in academia. Edward Sapir's study of the language was his doctoral thesis. It was so well done that it has been required reading in linguistic classes for decades. There are people in New York who have heard of -- and studied -- the Takelma language. Edward Sapir: The Takelma Language of Southwestern Oregon, 1922. [ PDF ] In November of 1933, John Peabody Harrington made two trips from the Siletz Indian Reservation to the Rogue Valley to visit Takelma places and gather cultural information. His main informants were Frances Johnson and Molly Orton. Also along on the trips were George and Eveline Baker, and their son Gib. On several occasions Frances and Molly mentioned Mary Eagan though it appears Harrington never interviewed her directly. Harrington's first trip was November 2-4, 1933 with Frances Johnson and Molly Orton. Frances was 98 at the time. Harrington then returned to Siletz, checked the accuracy of his notes, and came back to the Rogue Valley with Molly November 12-19. George, Eveline and Gib were along on both trips. From these trips, Harrington scribbled 1200 pages of field notes which have never been transcribed or published. I first got a copy of the field notes in the 1980s, and have been working with them ever since. Harrington's handwriting is often difficult to read. Sometimes I swear he was writing while driving! He also uses a number of cryptic abbreviations, many with variations. To put it mildly, it took a while to get "fluent" in the language of Harrington. To make the notes readable on this web page, I have used full words rather than Harrington's abbreviations, and I have standardized his spelling of place names. For Harrington, the notes themselves were a process. He often tried out various spellings of a name before deciding (sometimes hundreds of pages later) on the version "perfectly understood ... for all time." Sometimes Harrington updated previous entries in tiny margin notes on pages that have information not even related to the original topic. Finding one's way through the field notes is like visiting a new place in a wilderness where at first all the trees and clearings look alike, and it takes many days and walks before one notices the depths of differences and similarities. It's taken me over 30 years to get to that place, and yet still, with each reading, I discover something new. The best moments for me are the aha moments when I mentally connect the dots and some important piece of information becomes clear. Because Harrington's field notes seem to have a life of their own, this web page continues to be a work in progress. As the many mysteries contained in the notes get solved, I'll add new insights to this page. I have used the following notation to identify quotations from Harrington's field notes: (JPH: 781). JPH refers to John Peabody Harrington, and 781 the page number. The page numbers are the same as most scholars use, including Dennis Gray in his work The Takelma and Their Athapascan Neighbors. Gray's study is useful as a basic index for finding passages in the field notes. John Peabody Harrington: Field Notes [ PDFs ] Dennis Gray: The Takelma and Their Athapascan Neighbors [ PDF ] Through the village site of Ti'lomikh, the Rogue River flows roughly north to south. As the river primarily flows east to west from Boundary Springs to the coast, this north-south section of river often confuses people, and it certainly confused Harrington. He writes "north bank" and "south bank" in the field notes when in actuality he is referring to west bank and east bank. Then in an effort to be clear, he begins referring to the west bank as the "Willamette side" and the east bank as the "California side". Though his intentions are clear, this is still confusing to some people as the Willamette River is to the north and California to the south. For clarity, I have inserted the correct directions in brackets. Here are two examples from Harrington's field notes.... "Graveyard is upriver of powerhouse on north [west] high bank of river." "The Willamette [west] side man had something like iron in his forearm and smashed fish with it. Fisherman is there as a black rock on Willamette [west] side a little below the falls. Threw him on California [east] side." |

|

All Night Salmon Leap the Falls: Doty and Coyote meet the spirit of the poet called Lampman in an old house in the woods. The three of them walk back through time to participate in the Sacred Salmon Ceremony at Ti'lomikh, an ancient village along the Rogue River. |

During storms, the Rogue River at Ti'lomikh is roguish. Somewhere under the roiling river is Ti'lomikh Falls and the Story Chair, getting scoured and cleaned and ready for the spring salmon run.

|

Agnes Baker-Pilgrim, Stephen Kiesling and Thomas Doty were interviewed at Ti'lomikh by Alex Chadwick and Katie Davis, veterans of public radio. They tell the story of finding the Story Chair, a crucial part of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony. |

The winter lodges at Ti'lomikh would have looked much like this one. Inside, the floor is about two feet below ground level, with a firepit in the center, and sitting and sleeping ledges around the edges. This replica was built by Gray Eagle in honor of Takelma elder Agnes Baker-Pilgrim, and is located at the Kerbyville Museum in Kerby, Oregon.

Here's a video of Takelma elder Agnes Baker Pilgrim describing the lodge: Takelma Pit House.

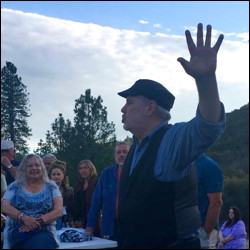

Takelma elder Agnes Baker-Pilgrim at Ti'lomikh in 2014.

|

George and Eveline Baker, along with their son Gib, accompanied John Peabody Harrington on two trips to the Rogue Valley in November of 1933, providing valuable information about the Takelma culture which Harrington included in his field notes. Harrington often stayed in their home in Logsden when he visited the Siletz Indian Reservation. George and Eveline were also the parents of Agnes Baker-Pilgrim. (Born in 1924). Grandma Aggie is a Takelma elder and spiritual leader. Her parents, George and Eveline Baker, and her brother Gib, accompanied Harrington when he visited Ti'lomikh in November of 1933. While Aggie didn't make the trip, she remembers Harrington in her home when she was a child. In 2007, as Keeper of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony, Grandma Aggie returned the ceremony to its original location at Ti'lomikh where it had been done for thousands of years. Frances Johnson was Aggie's great aunt. Aggie's Takelma name is Taowhywee, "Morning Star." Grandma Aggie passed away in 2019 at age 95. The traditional homeland of the Cow Creeks is located north of the Rogue Valley along the South Umpqua River and various streams, including Cow Creek. Though often referred to as Umpqua Indians, they are closely related to the Takelmas and speak the same language. Their Old Time name is Hanesak which refers both to the people and the land. Chuck Jackson was Tribal Chairman in the 1970s when the Cow Creeks regained their federal recognition as a tribe. Coyote is a trickster in many Native American mythologies, including Takelma folklore. In the story called "Daldal as Transformer," the Daldal brothers travel up the Rogue River making the world ready for the arrival of the Human People. When they get to Ti'lomikh, they find Coyote trying to fish for salmon but only catching mice, rabbits and gophers. The Daldal brother send Coyote on his way and establish Ti'lomikh as a salmon place and future home of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony. (1897-1994). A field archaeologist who is best known for his discoveries at Paleo-Indians sites such as Fort Rock Cave and Paisley Caves in Oregon. He founded the Department of anthropology at the University of Oregon and directed the archaeological digs at Ti'lomikh's main cemetery in 1930 and 1931. Daldal is a character in Takelma stories. While most native mythologies have a transformer or culture bringer character -- someone who transforms the world and makes it ready for Human People to live in -- nowhere else is the transformer a dragonfly. Or actually, two dragonflies! Near the beginning of the story called "Daldal as Transformer," Daldal splits himself in half and becomes Elder Brother and Younger Brother. Together they journey up the Rogue River, changing the world in various places, including Ti'lomikh. at the end of their journey, they turn into the Table Rocks, the center of the Takelma universe. (1911-1982). An American anthropologist and archaeologist who specialized in the Native American peoples of the Northwest Coast of North America. In southern Oregon, he worked primarily with coastal tribes, but included material gathered from Molly Orton in his published works, including a description of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony at Ti'lomikh. A Takelma who spoke a dialect of the Takelma language that differed from that spoken by Frances Johnson and Molly Orton. Mary is referred to by both Frances and Molly in Harrington's field notes but it is unclear if Harrington ever directly interviewed her. From Harrington's field notes: "Mary Eagan was from the place Hanesak.... Mary Eagan was both Frances' relative and Molly's relative. Mary Eagan was the one who taught Mrs. Eveline Baker how to talk jargon [Chinook Jargon, a trading language]." (JPH, 7: 0519). Mary Eagan was most likely a Cow Creek, a tribe to the north who also spoke Takelma and were closely related to Rogue Valley Takelmas. A Native American who provided cultural information to Harrington on 1933 trips to the Rogue Valley. Ned was half Takelma and half Shasta, and spoke both languages. A small town in southern Oregon located on a bend of the Rogue River. The ancient village site of Ti'lomikh begins on the edge of town and continues for a mile upriver. Grand Ronde Indian Reservation The Grand Ronde Indian Reservation is located in northwest Oregon near the town of Grand Ronde, and home to native people from a variety of tribes. While most Native Americans that were removed from their Rogue Valley homeland ended up at the Siletz Indian Reservation, some were sent to live at Grand Ronde. Harrington's native informant Molly Orton was born and raised at Grand Ronde. An area north of the Rogue Valley. In the 1980s, when I asked Chuck Jackson about the name, he said that it was the old name of the Cow Creek Indians. In his 1933 field notes, Harrington describes Hanesak as "Those distant blue mountains, seen through a gap between main [Lower] Table Rock and Upper Table Rock, are Hanesak. Jennie [Rogue River Jenny, Molly's cousin] told Molly there is a big waterfall there. But Jennie knows nothing of water from Hanesak coming around the east side of Upper Table Rock." (JPH: 658) [ PDF ]. And again: "Says that Hanesak is way up by blue mountains back of Sams Valley, far away, there is a big waterfall. and no salmon up there." (JPH: 706) [ PDF ]. I believe the blue mountains is the Rogue-Umpqua Divide, and the falls referred to is South Umpqua Falls. Chuck told me that since in the old days, the Cow Creeks have had their annual gatherings there, long before they were called powwows. Chuck also mentioned that when the fish ladder was built at the falls, the salmon went away. "The whites spoiled it," he said. (1884-1961). Harrington was a linguist and ethnologist. He specialized in the native peoples of California and was known for amassing "tons" of field notes, most of which has never been published. The shelf space in the National Anthropological Archives dedicated to his work spans nearly seven hundred feet. Harrington was described by colleagues and friends as obsessive and eccentric. He feared other anthropologists would steal his work, so much of it was stored in boxes in attics and post offices around the West, away from the eyes of prying scholars. In John Peabody Harrington: A Biographical Essay, Jane MacLaren Walsh writes: "The saddest thing about Harrington is that he never gave himself the time to enjoy what he was doing. He was driven beyond all understanding to copy down every word from every last survivor he could find, and once he had secured the best possible informant he would still spend sleepless nights worrying about how many others were dying at that very moment." MacLaren also tell this story: "Harrington's obsession with the collection of languages and the sorting out of sounds for their correct transcription is illustrated in the absurd by a story Henry Collins, archaeologist Emeritus at the Smithsonian, once told me. It involves A.V. Kidder whom Harrington met in the field, somewhere in the Southwest. Kidder came upon Harrington bent over a billy goat, grabbing him by the beard. When Kidder asked what in the world he was doing, Harrington told him to be silent and again pulled the goat's beard, exclaiming, "That's the most perfect umlauted A I've ever heard." In another classic Harrington moment, after hearing that one of his native informants had suffered a stroke, Harrington wrote to a colleague, "Do you suppose we can pep him up by giving him a shot of morphine to get him so he can talk before he dies????" Carobeth Laird, his wife of seven years, describes their painful relationship in her book, Encounter With an Angry God. Harrington made two trips to the Rogue Valley in November of 1933 with Frances Johnson and Molly Orton. Much of what is known about Ti'lomikh is contained in his unpublished field notes. Also known as Rogue River Jennie, Old Jennie, Table Rock Jennie and Lady Oscharwasha. "Jennie" is often spelled "Jenny." She was Molly Orton's cousin. In the latter 1800s, Molly often visited with her when her husband Steve had business in Jacksonville. Here is her obituary in the Ashland Daily Tidings for May 19, 1893: "LAST OF HER TRIBE -- Jacksonville, Or. May 14. -- Old Jennie, the last of the famous tribe of Rogue River, died here this morning after a protracted illness, aged about 65 years. Old Jennie, it will be remembered, anticipating her death, prepared with her own hands, in the most costly and elaborate manner, her burial robe, the material of which is of buckskin handsomely ornamented with many colored beads, sea shells, Indian money, beautiful transparent pebbles, etc., the whole weighing nearly 50 pounds. This death closes the last act in the sad drama of an historic tribe, then which no braver or more determined ever confronted and fell before the superior forces of civilization. Old Jennie was laid to rest in her burial robe this evening." Of course, Jennie was NOT the last of her tribe, and it is questionable whether the mix of miners, drunks, fur trappers and outlaws who played a major role in starting and perpetuating the Rogue River War were indeed "superior forces of civilization." Margaret LaPlante wrote about Jennie in her book, Jacksonville. The opening sentence refers to a famous photo of Jennie taken by pioneer photographer Peter Britt. "Indian Jennie is pictured here in her burial robe in Peter Britt's studio. As a young woman during the Rogue River War, Jennie and approximately a dozen other Native American women were instrumental in keeping the peace. The women were liaisons between the white soldiers at Fort Lane and the Native Americans. They tried to convince the Native Americans that even if they were triumphant, it would be short lived because the white settlers would continue to come into the valley and the Native Americans would be outnumbered. Gen. Lindsay Applegate credited the women for paving the way for the first peace treaty signed in 1853. Indian Jennie was one of the few members of her tribe who remained in the valley after the local Native Americans were led to the Siletz Reservation. Indian Jennie lived out her days in Jacksonville." Main source of language and cultural information for Sapir and Harrington. Frances was born in 1835, experienced the Rogue River Indian Wars as a young woman and walked one of the five Trails of Tears to the Siletz Indian Reservation. In 1906 she was interviewed at Siletz by Sapir, and she accompanied Harrington to Rogue Valley native sites in 1933. She was 98 years old at the time. Her native village was located north of Grants Pass along Jumpoff Joe Creek. She died in 1934 at age 99. Her Takelma name was Gwisgwashan, "Chipmunk Face." At Ti'lomikh, most of the Rogue River flows over Ti'lomikh Falls, and part of the rest flows down Mugger's Alley. There is evidence in Harrington's field notes to suggest that Mugger's Alley was a diversion ditch built by miners to redirect water around the falls.... "...whites made a ditch around one side of Rogue River, & spoiled the Ti'lomi falls." (JPH: 827) [ PDF ] Mugger's Alley is an important part of a world-class kayaking course, and gets its name from a tricky rock in the center that can easily flip kayaks and rafts. In other words, if you're running Mugger's Alley, don't get mugged! (circa 1790-1854). A fur trader and Canadian explorer of the Canadian and American West. Working for the Hudson's Bay Company, he visited Ti'lomikh in 1827, and kept a detailed dairy. He may have been the first European to visit the village. A Takelma from the Ashland area, and one of the main native informants for Harrington and Drucker. She was born and raised on the Grand Ronde Reservation. In the latter 1800s, she and her husband Steven moved back to the southern Oregon homeland of her ancestors. For a year she lived in a cabin at Ti'lomikh where she met Old Man Walker, perhaps the last Takelma living at the village in his ancestral home. This was on the east bank of the river at what would become known as Walker Rancheria. Molly's cabin was on the west bank, a little downriver. During her year at the village, she learned all about the village and the Sacred Salmon Ceremony from Walker, information she would pass on to Harrington when they visited there together in 1933. Molly and her husband also lived for several years in Phoenix, Oregon, and in 1887, she attended the Golden Spike Ceremony in Ashland which connected the north-south railroad lines in the West. She also spent time in Jacksonville visiting her cousin Jennie. Sometimes her name is written as Molly Orcutt. Molly claimed close kinship to Frances Johnson. In 1937, following Frances' death in 1934, Philip Drucker referred to Molly as "The last member of her people who has any recollection of the old culture." (1839-1927). George Riddle crossed the plains as an 11-year-old boy in 1851. It took the family six months to travel from Illinois to the Cow Creek Valley south of Roseburg, Oregon. On one night along the Rogue River, his family camped near Ti'lomikh and shared a salmon dinner with natives from the village. Sixty-five years later, Riddle described his adventures in a book, titled History of Early Days in Oregon. Riddle was elected Douglas County judge in 1890 and served several terms in the Oregon Legislature. He died at 87 as Superintendent of the Oregon State Soldiers Home in Roseburg. His younger brother, John Riddle, founded Riddle, Oregon in 1893. In his field notes, Harrington spends a lot of time trying to figure out the difference between Rocky Point and Rock Point, partly due to conflicting information given to him by local informants. It finally became clear that Rock Point (Titankh) is a few miles downriver where the old stage stop was (now Del Rio Vineyards & Winery), and that Rocky Point is within the boundaries of the village site at Ti'lomikh, just downriver of the falls.

To the Takelmas, the Rogue River is the lifeblood of the Great Animal that is the World, flowing through their homeland from Boundary Springs through the village of Ti'lomikh and on to the Pacific coast. The people call themselves Takelma, meaning "the river's people." (1884-1939). One of the foremost American linguists and anthropologists of his time, most widely known for his contributions to the study of North American Indian languages. Born in Germany, he was brought to the United States at the age of five. As a graduate student at Columbia University, he came under the influence of the noted anthropologist Franz Boas, who directed his attention to the rich possibilities of linguistic anthropology. For about six years he studied the Yana, Paiute, and other Indian languages of the western United States. A founder of ethnolinguistics, which considers the relationship of culture to language, he was also a principal developer of the American (descriptive) school of structural linguistics. Sapir suggested that man perceives the world principally through language. He wrote many articles on the relationship of language to culture. A thorough description of a linguistic structure and its function in speech might, he wrote in 1931, provide insight into man's perceptive and cognitive faculties and help explain the diverse behavior among peoples of different cultural backgrounds. He also did considerable research in comparative and historical linguistics. A poet, an essayist, and a composer, as well as a brilliant scholar, Sapir wrote in a crisp and lucid fashion that earned him considerable literary repute. In 1906, Edward Sapir visited the Siletz Indian Reservation and interviewed Frances Johnson. Four published works came out of this, including a highly-praised, in-depth study of the Takelma language. Notes on the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon, 1907 [ PDF ] Religious Ideas of the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon, 1907 [ PDF ] The Shastas are the southern neighbors of the Takelmas. Their traditional homeland is in northern California around Yreka and upriver into the Klamath River Canyon, and extending north over the Siskiyous and into the southern end of the Bear Creek Valley. They speak Hokan. While the Takelmas and Shastas intermarried, and several villages near their shared boundaries were populated with both, there were clearly times they didn't get along. The Takelma word for Shasta Indian is Wulx, meaning "enemy." The Siletz Indian Reservation is located on the north Oregon coast, a few miles inland from Newport. In 1856, following the Rogue River Indian War, most Takelmas were removed from their homeland, marched north, and forced to live on the reservation. As a young woman, Frances Johnson walked one of the five Trails of Tears to Siletz. In 1906, Edward Sapir visited Siletz and interviewed Frances about her Takelma culture and language. John Peabody Harrington visited several times in 1933. Lower Table Rock and Upper Table Rock are two mesa-like mountains along the Rogue River, a few miles upriver from Ti'lomikh. In the Takelma world view, they are the ribs of the Great animal that is the World, the center of the Takelma universe. They are also the Daldal brothers, the two dragonflies that traveled up the Rogue River to make the world ready for human beings. In 1853, a short-lived reservation was established on Lower Table Rock, but following the Rogue River War, Takelmas were removed to the Siletz and Grand Ronde reservations in northern Oregon. The traditional homeland of the Takelma Indians covers most of the Rogue Valley in southern Oregon, including north of Grants Pass to Sexton Mountain and south to Ashland. Their name means, "the river's people" referring to the Rogue River, the lifeblood of their world. Takelmas have lived in the Rogue Valley for thousands of years, and there is evidence that they were perhaps some of the first native inhabitants of the area. While their neighbors speak languages that are common in other parts of the country (Athabaskan, Hokan, Algonquin), the Takelma language is not related to any other language in the world. The Takelmas also have a two-layered system of lower class and upper class medicine people (goyos and somloholxas), and many myths and myth characters are uniquely their own and not found in neighboring tribes. Daldal the giant Dragonfly as culture bringer is found nowhere else in the country as are stories about Rock Old Woman and Coyote's Rock Grandson. Having studied Takelma culture, language and stories for 35 years, my gut feeling is that this is really old stuff. John Peabody Harrington: Field Notes [ PDFs ] Edward Sapir: Notes on the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon, 1907 [ PDF ] Edward Sapir: Religious Ideas of the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon, 1907 [ PDF ] Edward Sapir: The Takelma Language of Southwestern Oregon, 1922 [ PDF ] Ti'lomikh was a large Takelma village located along the Rogue River near what is now Gold Hill, Oregon. For thousands of years, the village was home of the annual Sacred Salmon Ceremony, the only first salmon ceremony in the region. The name Ti'lomikh (sometimes Dilomi -- see "The Takelma Language" on the web page) means "west of here live the cedar people." Lom is the Takelma word for cedar. The traditional village is a mile long, stretching from the main cemetery on the downriver end of the village, upriver past houses on both sides of the river, to the spring on the upriver end that provided fresh drinking water. It appears that the first European visitor to the village was Peter Skene Ogden in 1827. By 1856, following the Rogue River War and the forced removed of natives from their homeland, the village was pretty much abandoned except for miners and a few Takelmas who hid from the army and weren't sent to the reservations up north. In 2007, Takelma elder Agnes Baker-Pilgrim brought the Sacred Salmon Ceremony back to its home at Ti'lomikh, and it was done for the first time in over 150 years. The falls is located near the center of the village of Ti'lomikh and is the centerpiece for the Sacred salmon Ceremony. Thousands of salmon leaped the falls during the spring salmon run. The stone seat called the Story Chair, as well as the diving platform, are located at the falls and play an important role in the ceremony. The Old Time name of Ti'lomikh Falls (now the official name) is coming back into popular use, replacing a nickname that was used for years: Powerhouse Rapids. Tipulhukh is located on the west side of the Rogue River at Ti'lomikh Here a ridge from Beacon Mountain (now called Nugget Butte) runs down to the river at the downriver end of the village. There was once a flour mill there, and just upriver was the cabin where Molly Orton lived for a year in the latter 1800s. Old Man Walker was one of the last of the Takelmas living at Ti'lomikh. His Indian name was Eymehetkwat. When Molly Orton was living in a cabin at Ti'lomikh, Old Man Walker was living in his ancestral home, a little upriver near the falls. He "showed Molly the sites at Ti'lomikh where Indians used to live...." (JPH: 781) [ PDF ] |

Salmon baking at the Sacred Salmon Ceremony at Ti'lomikh, 2007.

|

The Rogue River: Lifeblood of the World From Crater Lake to the Coast Many years ago, during a time when I was spending a lot of time with Cow Creek elder Chuck Jackson, I scribbled these ideas into one of my notebooks.... To the Takelma people, the Rogue River is the lifeblood of the Great Animal that is the World. The head of the animal is Crater Lake, the neck is Boundary Springs where the Rogue River starts, the ribs are the two Table Rocks just upriver from Ti'lomikh, the rear end is Gold Beach where the Rogue flows into the Pacific Ocean. The river is also a symbol for the lives of the people. At Boundary Springs, the river gushes out of the hillside, becoming a full-blown river with a few yards. Suddenly. Like birth. Then fast as a child's growth, almost out of control, the river rushes down the slopes of the Cascades through Rogue River Gorge, through Takelma Gorge. In its middle life, the river flows past the Table Rocks, sometimes fast, sometimes slow. Then it widens and slows as it flows toward its death at the river's mouth at Gold Beach. But that's not the end of the cycle. Clouds form over the Pacific which move inland over the Cascades which brings rain and snow that feeds the springs that feed the river. An eternal cycle, and a symbol for the lives of the native people. In Religious Ideas of the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon, in a footnote to a medicine formula that contains the line, "Yonder alongside the earth's rib," Edward Sapir writes: "The earth is conceived of as a vast animal lying on its belly and stretched out towards the east." In the vocabulary list in Takelma Texts, Sapir lists Gelam as meaning "river" and Dagelam as meaning "along the river" and he makes a note that this means specifically the Rogue River. Then, in Notes on the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon, Sapir writes that ... "Dagelman [Takelman -- brackets are mine] means 'one who comes from Dagelam,' or Rogue River, i.e. Takelma Indian." (1) Since the Old Time, when Daldal, the transformer and culture bringer, traveled up the Rogue River to prepare the world for the Human People, the Takelmas have had a close relationship with the river, so close, in fact, that there are only two directions in the myths. Everything is either upriver or downriver. This relationship with the river plays itself out each year in honoring the chief residents of the river, the Salmon People, at the annual Sacred Salmon Ceremony at Ti'lomikh. Notes (1) Put simply, the Takelma word for the Rogue River is Gelam (or Kelam if we use Harrington's system). This word is contained within Takelma, the word the people have for themselves, which means, "the river's people." Sources Doty, Thomas. Unpublished Field Notes. Harrington, John Peabody. The Papers of John Peabody Harrington in the National Anthropological Archives of the Smithsonian Institution. Unpublished Manuscript. 1907-1957. [ PDFs ] Sapir, Edward. Notes on the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon. American Anthropologist, Vol. 9, #2, 1907: 251-275. [ PDF ] Sapir, Edward. Takelma Texts. Anthropological Publications of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 2, 1909. [ PDF ] Ti'lomikh Established as a Salmon Place Here is an excerpt from "Daldal as Transformer," a Takelma myth establishing Ti'lomikh as a salmon place, and future home of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony. The story was told by Frances Johnson to Edward Sapir at the Siletz Indian Reservation in 1906. Now Coyote snatched up the fishing-net. "In the water I shall catch salmon," Coyote thought to himself, but he caught only mice in the fishing-net. Again he threw it forth into the water, but caught only gophers. "Eh! you shall not catch salmon," he was told. "In the earth you shall hunt gophers, mice, for your part, catch," did Daldal (1) say. Then he said, "People shall spear salmon, they will go to get food, to one another will they go to get food; one another they will feed, and they shall not kill one another. In that way shall the world be, as long as the world goes on." Then, 'tis said, they continued on their way. These things he had said at Dilomi, (2) in front of the falls he had said so. Right there salmon are always caught in fishing-nets. Notes (1) Daldal is a giant dragonfly, and Takelma transformer and culture bringer. The Daldal myth is an episodic myth. As long as the storyteller gets the beginning and ending right, and in place, she can make the story longer or shorter simply by adding or removing episodes. Traditional native storytellers are deeply tuned in to their audiences and give them precisely what they sense they need. I suspect that there were more episodes in the Daldal story than were recorded. (2) Dilomi (Sapir) is a linguistic variant of Ti'lomikh (Harrington). See "The Takelma Language" in the Introduction. Salmon People Live in Underwater Houses When Philip Drucker was gathering folklore from Northwest tribes, he came across quite a lot of common beliefs concerning the importance of salmon, and ceremonies and rituals to honor the Salmon People. Drucker also discovered a fairly generalized salmon about the salmon People living in houses at the bottom of the sea which I have heard Grandma Aggie tell at Ti'lomikh. I have included Drucker's synopsis of the story as well as his insights on the background of the story. A set of beliefs relating to the immortality of certain animal species was universal throughout the Northwest Coast. It seems fairly clear that in most cases the original concept, regardless of the group of groups of its origins, probably referred specifically to salmon. When one considers the spectacular phenomenon of the annual salmon runs, such a belief seems reasonable enough, especially to primitive people. At the same season every year, the same one of the five varieties of salmon would appear in great numbers in the bay or cove at the mouth of some stream, and after a short time, would start upriver. A relatively small number, of course, were harpooned, netted, or trapped, but the majority proceeded to the spawning grounds far upstream, spawned, and died. Their lean, battered bodies lined the river banks and drifted back to the sea. It is doubtful whether the Indian understood the life cycle of these fish, or connected the spawning with the tiny new-hatched parr, or these with the adult salmon. (1) Yet the following year the species appeared again. Hence, what could be more logical than the concept that the salmon ascended the streams to benefit mankind, died, and then returned to life? The general belief was that the salmon were a race of supernatural beings who dwelt in a great house under the sea. There they went about in human form, feasting and dancing like people. when the time came for the "run," the salmon-people dressed in garments of salmon flesh, that is, assumed the form of fish to sacrifice themselves. Once dead, the spirit of each fish returned to the house beneath the sea. If the bones returned to the water, the being resumed his (human-like) form with no discomfort, and could repeat the trip next season. Since the Salmon-people's migration was considered to be voluntarily undertaken, it behooved human beings to take pains not to offend their benefactors. To return all the salmon bones to the water was one of the procedures believed to be essential. (2) If some bones were thrown away on land, on resurrection the Salmon-person might lack an arm or a leg, or some other part, and he and his tribe would become angry and refuse to run again in the stream in which they had been so unappreciatively treated. All the Northwest Coast groups had long lists of regulations and prohibitions referring to the Salmon-people in order to continue to maintain good relations with these important beings. This concept was extended to many other species. Herring and olachen, also seasonal species, were widely believed to have their own house under the sea (or to share the Salmon-people's house) and to behave the same way. The Nootka believed that whales, hair seal, and on land, the wolves, (not of economic, but of ritual importance) likewise had their houses, and emerged wearing their animal form like a replaceable garment. Even creatures who were not believed to live in "tribal" houses were considered immortal. Among the Yurok, and probably their neighbors as well, deer were thought to be resurrected in the same fashion, and it was believed that they deliberately entered the snares or exposed themselves to the fire of hunters who meticulously observed the rites the Deer-people considered pleasing. It was not only the beliefs themselves that unified a great part of the areal religious patterns but also the rites and observances developed out of them. For example, a First Salmon ceremony was held over the first catch from each important stream or area, the purpose of which was to honor and to welcome the first of the species. Usually the fish was addressed as though it were a visiting chief of high rank; it was handled in a ceremonial way, and was frequently given offerings such as the sacred eagle down of the northern groups; it was cooked and eaten in a formal fashion. This type of rite, except for details in performance, was almost uniform everywhere, except at the very extremes of the area. Tlingit and Haida attached less importance to it, and performed it in a more attenuated fashion than did their neighbors to the south. In northwestern California the ritual was integrated with a First Fruits rite (and, among the Karok [Karuk], with a New Fire ceremony) and, as well, with the Wealth Display performances, into a cult-system that has been designated a World-Renewal cycle. Nevertheless, the First Salmon ceremony was performed in some form by all groups of the coast, and even by a few of their peripheral and ruder neighbors of the interior. Notes (1) I disagree with Drucker's observation. There are several native stories in the Northwest that dramatize the life-cycle of fish. Also, the central idea of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony is to allow thousands of salmon to swim past the village to go upriver to spawn to ensure that there would always be salmon. It seems to me that an understanding of the life cycle of the salmon was necessary to create this complex ceremony. (2) In the Takelma Sacred Salmon Ceremony, divers return the bones and skin of the first salmon to the bottom of the pool beneath the falls, back to the source. Evening Star & Morning Star In February of 1936, two years after the death of Frances Johnson, Philip Drucker interviewed Molly Orton at the Siletz Indian Reservation. Details of this interview were included as an Appendix in his study on the Tolowa and their neighbors. At a place now called Rocky Point (1), the people assembled in summer for salmon fishing. "This was big-time, like Fourth of July. This was the time salmon have sore backs." A dance similar to the Athabaskan wealth-display performance was often performed. An old man trained for some days, then, with a dip net, caught the first salmon of the season in a large pool below a waterfall. He dressed and cooked the fish, and told the story of the origin of the fishing-place. The first owner of the place (Evening Star ?) challenged all who came there to a wrestling match, and killed them. He allowed no one to fish. At last someone (Swallow ?) managed to vanquish him, "and gave the salmon to be free to all the people." (2) The ritual was performed to make the salmon safe for people to eat. This was said to have been the only place in the region where a first-salmon rite was performed. (3) Notes (1) Rocky Point should not be confused with Rock Point which is several miles downriver from Ti'lomikh. Rocky Point refers to the rock ridge that runs down from Beacon Mountain (now called Nugget Butte) to the Rogue River, a little below Ti'lomikh Falls. Harrington made several references to the distinction in his field notes and put a lot of effort into getting it right. (2) The myth fragment seems to be Molly's attempt to remember an episode in "Daldal as Transformer." In Frances Johnson's version of the story as recorded by Sapir, she mentions that Elder and Younger Daldal come across two wicked brothers at Ti'lomikh who were hoarding salmon. Daldal turned them into Evening Star and Morning Star: "Do you think you that you will be a person?" and to the west he threw him. "The Evening Star you shall always be called, you shall always be called he that comes up in the evening." (To the younger one he said, "You will be) he that comes up in the east early in the morning." Right after this episode, the Daldal brothers come across Coyote fishing for salmon. In Harrington's field notes there is yet another version of this story scribbled onto a map as two separate (and somewhat confusing) entries, and yet a third version in text on the next page. The bad man would not let anyone fish there. The Willamette [west] man told him as he threw him into river he would turn rock. He floated downriver and turned to rock came out on the Willamette [west] side & the rock is there somewhere on Willamette [west] side. The Willamette [west] side man had something like iron in his forearm and smashed fish with it. Fisherman is there as a black rock on Willamette [west] side a little below the falls. Threw him on California [east] side. (JPH: 814) [ PDF ] Old walker told the story. Tepila, a blue stone high as a man (has?) a chair, 2 feet high, he would invite other men to get fish & then suddenly, a man came from Willamette [west] side & heard it was a bad man. "can you wrestle?" They wrestled. He got him in the ribs. "Oh, dam sick." He threw bad man in river, in deep water. The Willamette [west] side man was skookum. (In margin: must be blue slate. He was fishing with dipnet -- it took 2 men to lift it.) (JPH: 815) [ PDF ] (3) Earlier in his study, Drucker mentions a salmon ritual done by the Athabaskan speaking natives who lived along Galice Creek, a tributary of the Rogue River, and several miles downriver from Ti'lomikh: "A first-salmon ceremony, consisting of the recitation of a formula and the ceremonial feeding of each of the spectators by the priest, was reported." Sources Sapir, Edward. Takelma Texts. Anthropological Publications of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 2, 1909. [ PDF ] Drucker, Philip. Indians of the Northwest Coast. Garden City, New York: The Natural History Press, 1963. Drucker, Philip. The Tolowa and the Southwest Oregon Kin. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 36, #4, 1937: 221-99. [ PDF ] Two Story Chairs The two stone seats at Ti'lomikh are called Story Chairs. Both were used for fishing and have grooves carved along the seat for holding the handle of a dipnet. However, during the Sacred Salmon Ceremony, one chair was used for catching the first salmon of the spring run, and the other as a seat for storytellers telling Old Time stories about Ti'lomikh and the Salmon People. The chair carved in bedrock by the falls is the only one that has survived. The second chair was portable, and probably disappeared during the hydraulic mining operations of the 1800s or was swept away during the 1964 flood. On January 26, 2007, Stephen Kiesling, Kim Marie Murphy and myself waded through the icy Rogue River and found the Story Chair by the falls. When John Peabody Harrington, Molly Orton, and George, Eveline and Gib Baker visited Ti'lomikh on November 16, 1933, Molly identified a small, portable Story Chair located on the east edge of the river. Meanwhile, George Baker crossed a slippery plank to the falls and found a second Story Chair, this one a stone seat carved into bedrock. Here are Harrington's notes.... Reacht it & parked the car between road & river, on very edge of a high bank of stuff almost as hard as puddingstone. (1) She [Molly] recognized the place as the fall, & located the story chair at the south [east] edge of the river, at foot of this bluff. In a channel somewhat out in the river from the south [east] bank and reached only by crossing on a slippery plank & then going downriver over some rocks, is the main fall. George Baker went to it and said there is a seat there, like a place shaped to the two buttocks of a very large fat man, with places below to put one's feet, and a notch at right side for putting the pole of a dipnet, and facing a little upriver of straight towards a good fishing eddy, just below the best fall. I called attention to George sitting in the stone & Molly and Eveline got a good look at him. When we told Molly about the chair which George had found, she said that is a different one. She explained in clear words that the chair that she saw is a portable blue-colored rock, and had a groove at the left side of the chair into which groove the pole of the dipnet would be inserted to hold while the fisherman went to dinner, (2) Walker explained to Molly. The rock was down the bank at the south [east] edge of the river, one did not have to cross water to go to the chair. But the chair that George had found is a seat in bedrock, with groove on right, and has to be reacht by crossing a channel of the water. (JPH: 678-80) [ PDF ] There is a high steep rock-bank on California [east] side there, & the story chair was on the edge of water at foot of this bank. A man would sit on that chair & fish for salmon with a dipnet, and soon it would be so heavy with salmon it would take 2 men to lift it out. (JPH: 683) [ PDF ] Seat itself [the Story Chair George found by the falls] is 20" wide, 18 from back to front. 14" from seat to foot resting place. The total width of chair formation is 42". It faces south, just a little to right of downriver. Seat of chair is 6 or maybe 7 feet from present water, straight elevation. It is 50 feet downriver of foot of the fall. The fall drops 6 feet or more in 20 feet distance. Foot of fall is 20 feet wide. Gorge below the fall is 90 feet long, 25 feet wide, the top of the passing water & top of the rocks on each side is ... 8 feet. (3) (JPH: 708) [ PDF ] Notes (1) This is the gravel turn-out along Upper River Road which has a view of the falls, commonly called the overlook. (2) Or paused to tell a story to people who had gathered at the Sacred Salmon Ceremony. (3) These days, to avoid confusion, the stone chair near the falls is called the Story Chair, and a larger stone on the overlook that replaced the lost portable chair on the riverbank is referred to as the Storytelling Stone. Reciprocity Many years ago, the Takelmas made a deal with the Salmon People. The Salmon People provide food for the people, and in return, the Takelmas will ensure that the salmon species thrives. (1) This bargain has its foundation in reciprocity. To celebrate and renew this agreement, each spring during the spring salmon run, the Takelmas host the Sacred Salmon Ceremony at Ti'lomikh. Since this was the only one in the region, hundreds of people came from all around to attend. as Molly Orton told Philip Drucker, "This was big-time, like Fourth of July." After years spent talking with elders and ancestors, and just as long consulting the literature, I have pieced together what I believe is a fairly accurate description of the ceremony as it happened for thousands for years at Ti'lomikh.... The ceremony lasts for five days and nights. The Takelma sacred number is five. Visions quests, feasts and ceremonies last for five days and night. In the myths, good things happen in fives. This is common throughout Oregon and into northern California. For a few days prior to the spring salmon run, an elder fisherman sits in the Story Chair by the falls, dipnet in hand, and waits for the first salmon to approach the falls. Perhaps he saw it coming, or maybe he got word from folks downriver. The first salmon is netted, and quickly gutted and put on a drying rack. Then for the length of time it takes for that salmon to dry, no more salmon are taken from the river. This allows thousands of salmon to swim past the village, leap the falls, and continue upriver to spawn to ensure there would always be salmon. Depending on the weather, this might take a few days. Meanwhile, five divers have been participating in a sweat ceremony to purify themselves and prepare to dive into the pool below the falls. They wrap the bones and skin of the first salmon in cedar -- Ti'lomikh means "west of here live the Cedar People" -- and one by one they make their way to the stone platform above the Story Chair. Everyone in the village is silent. They line the riverbank to watch the divers dive from the platform into the pool, swimming down to leave the bones and skin in sand at the bottom, returning the first salmon to the source, the river that is the lifeblood of the world. The divers make their way back to the village to the sound of flutes, welcomed back by everyone in the village. As the people wait for the first salmon to dry, games are played, songs sung, dances danced ... all to celebrate the arrival of the Salmon People. Storytellers take turns sitting in the stone Story Chair on the riverbank, sharing stories of the salmon and the village and the people. The myths dramatize the rituals that have been acted out in the village and out by the falls. When the first salmon is dry, the people go fishing. Salmon are baked on redwoods stakes around a sacred fire. And on the fifth night of the ceremony, a salmon feast is enjoyed by everyone. More songs. More dances. The people have their food, and upriver, thousands of salmon swim toward the spawning grounds to ensure that myth and ritual, food and survival, happen again next year. And the next. And the next. Notes (1) "The general belief was that the salmon were a race of supernatural beings who dwelt in a great house under the sea. There they went about in human form, feasting and dancing like people. When the time came for the "run," the salmon-people dressed in garments of salmon flesh, that is, assumed the form of fish to sacrifice themselves. Once dead, the spirit of each fish returned to the house beneath the sea. If the bones returned to the water, the being resumed his (human-like) form with no discomfort, and could repeat the trip next season. Since the Salmon-people's migration was considered to be voluntarily undertaken, it behooved human beings to take pains not to offend their benefactors. To return all the salmon bones to the water was one of the procedures believed to be essential." (Philip Drucker. Indians of the Northwest Coast. Garden City: The Natural History Press, 1963.) The Ceremony Returns In 2007, for the first time in over 150 years, Agnes Baker-Pilgrim, Takelma elder and Keeper of the Sacred Salmon Ceremony, returned the ceremony to Ti'lomikh. Hundreds of people gathered to watch the divers return the bones and skin of the first salmon to the bottom of the pool below the falls. Stories were told. There was singing and dancing. Salmon baked on redwood stakes around the sacred fire. An ancient agreement with the Salmon People was honored. In 2012, Grandma Aggie visited the Story Chair by the falls, the same stone seat her father George Baker had visited in 1933. More Info: Sacred Salmon Ceremony Sources Baker-Pilgrim, Agnes. Takelma Elder. Personal Conversations with Thomas Doty. Doty, Thomas. Unpublished Field Notes. Harrington, John Peabody. The Papers of John Peabody Harrington in the National Anthropological Archives of the Smithsonian Institution. Unpublished Manuscript. 1907-1957. [ PDFs ] Drucker, Philip. Indians of the Northwest Coast. Garden City, New York: The Natural History Press, 1963. Drucker, Philip. The Tolowa and the Southwest Oregon Kin. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 36, #4, 1937: 221-99. [ PDF ] Jackson, Chuck. Cow Creek Elder. Personal Conversations with Thomas Doty. 1792-1826 While the first recorded meeting between Whites and Indians of southwest Oregon was in 1792 during the expedition of British explorer George Vancouver, native people had already felt the disastrous effects of smallpox epidemics as early as the 1770s, all along the Oregon Coast, and even as far inland as the Rogue Valley. Soon after, the first native people would be killed by whites at Rock Point, just a few miles downriver from Ti'lomikh. This was a couple of decades before miners and settlers arrived, and the Rogue River War of the 1850s. E.A. Schwartz, in The Rogue River War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980, chronicles early encounters between Whites and Indians.... The destruction of the Chetco towns in 1854 (1) was one incident in a long series of confrontations between Indians and non-Indians in southwestern Oregon. Some whites recognized that the excesses of certain of their compatriots fueled the chronic violence in the region. But the violence provoked white fear and promoted the reputations of the inhabitants for merciless savagery. The name non-Indians gave to the principal river of southwestern Oregon, the Rogue River, dignified the reputation of the peoples who lived there. Jesse Applegate, a pathfinder of the American occupation of southwestern Oregon, claimed in 1851 that Canadian traders had begun calling the Indian peoples the "Rascals" because of their disregard for the laws of property, "hence the name of "the Rascal or Rogues river." But there was no killing, Applegate said, until they encountered a party led by the American trapper Ewing Young in 1834. Applegate was mistaken. Members of a Hudson's Bay Company party that passed through the valley not long before Young were the first outsiders known to have killed Rogue River valley people. They were led by Michel Laframboise, and they were said to have killed eleven Indians in a confrontation while suffering no losses of their own. In the case of the Young party, by Jesse Applegate's account, Young ordered his men to fire on Indians who had tried to take meat from a drying scaffold, and "terrible slaughter of the unprepared natives ensued." The sole injury among Young's men was a serious bite received by one of the men while stripping the skin from the head of an Indian not yet dead." Only since the Young expedition, according to Applegate, had the Rogue River people been hostile to whites. One of Young's men told another version of the massacre. When the Young party reached the Rogue River, he said, several of its members were suffering from malaria. Two Indians who visited the camp were killed to keep them from telling others how vulnerable the sickness had made the trappers. The 1834 encounters of Indian people with murderous trappers followed at least forty-two years of contact during which no one was recorded killed, and no non-Indians would be killed until 1835. Notes (1) Schwartz is referring here to an incident near the mouth of the Winchuck River. While most of the native people were out hunting and gathering nuts, whites entered their village and burned forty houses and the old people in them. 1827: Peter Skene Ogden In 1827, Hudson's Bay Company fur trapper Peter Skene Ogden and his company camped for a week along the Rogue River near Ti'lomikh. At this time, the Hudson's Bay Company's mission was to send trappers like Ogden out to unexplored territories to trap as many beavers as possible before competing trappers showed up. This was done at any cost, and native people often paid the price. Here are excerpts from Ogden's journal, beginning with a description of the Bear Creek Valley near Ashland just before Ogden traveled down the valley, crossed Bear Creek and started downriver along the Rogue River. As far as I know, Ogden was the first European to visit the Rogue Valley and keep a journal. I have included journal entries here that give his impressions of the people and the land upriver and downriver of Ti'lomikh. After camping for a week a bit upriver of Ti'lomikh, Ogden arrives and first sees Ti'lomikh on March 1. For clarity, I have inserted periods where sentence breaks are obvious with capitalized letters following. Ogden's journal is sparse when it comes to punctuation. I have retained his spelling. An accurate and useful source for Ogden's journal is First Over the Siskiyous by Jeff LeLande. He includes maps and excellent commentary based on his insightful research. In the following text, notes in brackets are LaLande's. February 10, 1827 ... this morning fine warm weather. We started at 8 A.M. and proceeded on untill 2 P.M. when we encamped on a large Fork form'd by a number of small Streams which we crossed in our travels this day. And in many of them not long since there were Beaver ... this is certainly a fine Country and probably no Climate in any Country equal to it, the Indians inform us the winter is now over and I am almost inclined to believe them from the singing of Birds of all kinds, grass green and as its full growth Flowers in blossom certainly entitles them to be credited but we are yet in February. With the exception of Mountains which appear at some distance from us the Highest Hills are without Snow. If we may judge from heat at present how it is in Summer certainly then it must be great. From the dry state of the roads it does not appear as they are annoyed with rain but probably all seasons are not alike. Be it so but at present it is certainly fine weather and certainly a country well adapted from its Soil and timber (Oaks and Pine) for cultivation. The natives inform us that Deer are abundant in the hills and Mountains ... from their being well clad in leather I can believe them ... Arrow quivers made of Beaver Skins also their Caps ... they were most anxious in directing where to find them observing there were but few in the small Streams but in the large River they were numerous ... so far as I could see in advance there was not the appearance of any ... Here we are now amongst the Sastise or (Castise) it was this Tribe that was represented to our party of last year and also to us as being most hostilily inclined towards us. So far we cannot say what their intentions may be. We have not seen more than 30 and their conduct has been friendly.... Course this day West. Distance 15 miles. February 14: One of the trappers yesterday saw a domesticated Cat in a rather wild state. He endeavored to secure it but in vain. I presume it must have come from the Coast. In that quarter all along they are in almost every village a dozen of them. But how this one found its way in this distant quarter for all the Indians still persist in asserting they know nothing of the Sea ... he must certainly lead a solitary life ... but field mice are numerous all over the plains. February 15: Fine clear weather, this morning the Horse Keeper in collecting his Horses found one kill'd and three wounded by arrows.... From our want of knowledge of the Country we are in and the Trapper scattered in different directions prevents me at present from making an example of some of them. The only alternative left at present for us is to commence again our night guard ... they certainly evince a most malicious disposition towards us and if not checked and that soon our Scalps will soon share the fate of our Horses.... we loaded our Horses and at 9 AM we started still following down the Fork when within a mile of its discharge in a large River equal in size to the Willimatte we cross'd over [to the west side of Bear Creek] and soon after reached it [the Rogue] and when we descended for four miles when the Trappers informed me I was in the advance of their Traps we of course encamped, we made a long days march having travelled from nine in the morning until five in the evening. But the distance was not in proportion to the time from the state of the roads. worse they cannot be the last three days of rain have done them no good ... This is certainly a fine looking Stream well wooded with Poplar aspine and Willows and from its depth it must be well supplyed with tributary Streams or its rise must be far distant. We shall in course of time ascertain it -- this River I have nam'd Sastise River also a mount equal in height to Mount Hood or Vancouver [Mt. Jefferson] I have nam'd Mount Sistise ["Sastie"] its bearings by our Compass from our present encampment East South East. I have given these names from the Tribe of Indians who are well known by all the neighboring Tribes ... by giving English names it often tends to lead strangers stray.... we travelled over a fine level Country and on reaching this River we saw two small Herds of White tail Deer ... Distance this day 15 miles. Course West North West ... One of the trappers reported ... he met with three Indians who on seeing him strung their Bows and mad[e] preparations for sending him a few Arrows.... at this Season dead salmon are most numerous in all the Small Rivers and the Natives are busily employed in collecting them no doubt for food.... The Indians even go so far as to select them in a putrid state giving them the preference. What a depraved taste.... February 16: The rivers are rising fast. The Trappers are alarmed. They have visited a Small Fork near by. Found a few Beaver. Complain of the unsteady state of the Water and Natives most numerous bold and Insolent ... they appear determined to oblige us to leave their Country. February 17: Some Traps were visited but those beyond the forks [the confluence of Bear Creek and the Rogue?] the Trappers could not reach them the Water having risen nearly three feet perpendicular and in the main Stream, it fell in the same proportion. But should we have two days of fine weather it will rise rapidly and the Small forks will fall in proportion.... we sent one of our [Shasta] Guides to discover the Indians and by fair means induce some of them to our Camp so as to obtain some information from them relative to the Country for beyond this in any direction our Guides are entirely ignorant. February 18: Three men commenced in making a Canoe and I am in hopes they will complete it tomorrow so as to enable them to crooss [cross] over to sett the Traps, there is a fine large Fork on the opposite side a short distance from this and we are in hopes of finding Beaver in it. Our messenger returned from his errand and informs us the Indians will assemble and pay us their respects tomorrow ... from their late conduct they appear to wish to remain at variance with us.... Day after day passes and still no accounts ... of our absent men. February 19: Our expected Indians did not make their appearance -- the men finished their Canoe and cross'd over the River also four more on Rafts ... waters are now gradually subsiding.... Numerous Flocks of wild Fowl consisting of Grey and White Geese Bustards & Swans pass'd by bending their course to the Westward. February 20: Beaver fur can almost be compared to Summer Beaver.... Ten Indians paid us a visit. They denied having any knowledge or being any ways concerned in the killing of our Horses and express a wish to remain at peace with us. February 21: Late last evening I was pleased to see seven of the nine absent men make their appearance but their success has not been so great ... only 73 Beavers 9 Otters. February 22: Last evening upwards of fifty Indians assembled near the Camp and sent two men in advance to inform us they wished to make peace with us. They received our consent and soon after made their appearance. This affair was soon settled at the expense of two Dozen Buttons.... After this ceremony was concluded they amused the Camp with a dance. In this they acquitted themselves as well as Indians ever did.... We have this day 15 Beaver which completes our first thousand and leaves us eight to commence our second with.... The Indians in this quarter give us no hopes of find any but inform us as we descend this River your progress will soon be arrested by I suppose the same chain of mountains our party had to contend with. It may be so but at present we must examine the upper part of this Stream before we think of descending. March 1: We had a rainy night but a fine day. At an early hour we were in motion and at nine Mr. McKay with 13 men separated from us.... At 11 A.M. we started. My party now numbers 24. On starting we left the River taking an East [mis-copy for "West"] Course two miles when we crossed over a long point and 1 P.M. we again reached the main Stream amongst Falls and Cascade. On the opposite side we saw a large Village containing six large Houses sufficiently so to contain upwards of 100 Indians but on seeing us preparing to encamp opposite their Village they soon left and ascended the hills with their Children and property.... We had but a few Traps sett the greater part from the sudden rising of the water last night nearly 2 1/2 feet perpendicular could not be found.... Distance this day six miles. Worse roads cannot be found -- the River appears to take a South West Course. (1) March 2: This day commenced with rain and continued all day. We did not attempt starting.... Some of the men who succeeded in crossing the River yesterday went to the Village. They found only two men remaining with one Woman, in their village they saw a sickle and two China Bowls. From whom they procured these article we could not learn ... have travelled from the Coast and probably procured from some Ships passing by. They would not part with either appearing to lay considerable value on both, this is certainly a convincing proof they or Tribes not far distant have had intercourse with Ships or Tradors but in my opinion with the former or probably with the Spaniards in some of their trading excursions have ascended a part of this Stream. But as we advance we may see more and obtain more correct information ... some distance below there is a large Fork which from appearance we are in hope of finding Beaver. The Country on the opposite side is also less woody and hills and Grass more abundant. During the night the water fell 14 inches and this day it has risen ten perpendicular. March 3: Fair or foul tomorrow we must start otherwise we must start killing our Horses for food. One of my men by orders swam across the River and after a long search succeeded in finding a Canoe which he cross'd over leaving the full value of it in the same place ... the owners will find and give them a favorable opinion of our good intentions.... In the afternoon six men started in advance with Traps and two with their Rifles in quest of Deer. March 4: At ten we started and followed down the Stream and continued descending until 2 P.M. when we reach'd a large Fork on the opposite side of the River and encamped. Notes (1) Though scholars and historians generally agree that Ogden camped at Ti'lomikh on March 1, it's not clear where exactly he camped and which houses he saw across the river. At that time, the village was a mile long with houses on both sides of the river. Most likely he left the Rogue River upstream of the village and traveled around the southern base of Blackwell Hill, roughly following the route of present-day Interstate 5, and then rejoined the river near the mouth of Kane Creek, setting up camp next to the village cemetery. 1851: George Riddle When George Riddle was 11 years old, he traveled by wagon train with his family from Illinois to Oregon. In 1851, they camped near Ti'lomikh. I include Riddle's description to show that all encounters between whites and natives were hostile. At the time we passed through the Rogue river valley there were no settlements of any kind and we met no prospectors, but later in the fall of 1851, gold was discovered at Jacksonville, which caused that country to settle up quickly in 1852. We met with very few Indians in the Rogue river country and those we met were friendly. I recall that at our camp on Rogue river, directly opposite Gold Hill (when I give the name of places in this story, it is the present name), we were visited by Indians that brought some splendid salmon for trade and we all had a feast of that king of fish.