Thomas Doty – Storyteller

|

|

A Reburial of Artifacts and Bones

In the 1980s, there was a museum in my hometown of Ashland, Oregon that sold Indian artifacts. When John Kelly and I had some extra coins, we wandered in and bought a few arrowheads. That night, on one of our midnight saunters up Lower Table Rock, we buried the arrowheads in a quiet, moonlit ceremony. We returned these descendants of the Rock People back to the Ribs of the Great Animal that is the World -- the center of the Takelma universe. We heard the night breathe deep, and we sensed that this ancient rock mesa was grateful that a few relations had come home. Eventually, the museum went bankrupt and closed its doors.

One of the elders John and I learned from was Chuck Jackson, tribal chair of the Cow Creek Indians. Every few weeks we drove over the Rogue-Umpqua Divide to Chuck's home. We listened to Chuck's wise stories for hours. In addition to being a great storyteller with a vast knowledge of cultural traditions, Chuck was also a deep listener. He patiently listened to us relate each of our adventures on Lower Table Rock, or some other sacred place in our homeland. Sometimes Chuck sat quietly. At other times he whispered an insight with a few carefully chosen words.

One of Chuck's many accomplishments was when he wrote Oregon's reburial law, the strictest in the country. It required that when human remains were unearthed, they were reburied with ceremony. Not only were the bones reburied, so were all of the artifacts from the original grave. They weren't sent to museums or scooped up by collectors. They went back in the ground.

I attended one of Chuck's reburials at Hanley Farm near Jacksonville. During an expansion of one of the gardens, workers came upon an ancient grave. It was filled with artifacts ... a stone pipe, an obsidian knife, a necklace of pine nut beads, and much more. Word got out, and amateur archaeologists crowded around Chuck. The pipe and knife alone could bring a small fortune on the black market.

The group was quiet while Chuck prayed and sang, gently placing the bones in the new grave. When he picked up the pipe, he looked up and said, "Now you good old boys aren't going to come back here and dig this poor fellow up, are you?"

Several whispered "No" and shook their heads, but their eager and curious expressions gave away their intentions.

"That's what I thought," said Chuck. To the everyone's astonishment, he smashed the pipe on a rock! It took Chuck half an hour to carefully place each shard into the grave, whispering the whole while, "It's all there, isn't it? It's all there."

A cloud of irony floats over my memory of that day. In the years since, the Southern Oregon Historical Society -- owner of Hanley Farm -- has become the area's largest hoarder of Indian artifacts, thousands stuffed into a giant warehouse that is not open to the public or the tribes ... out of sight, and mostly out of mind.

Most folks understand that Indian graveyards, ceremonial sites and ancient villages are considered sacred by native people. They should be visited with care and respect, and always left undisturbed. But I believe that the notion of what is a sacred site is more expansive.

Chuck explained it to me this way. "White people think we just abandoned the artifacts and left them scattered around. Most were left there on purpose."

He went on to explain that some were caches of tools to be used on the next seasonal round. Mortars and pestles were left where nuts and seeds were gathered, and fishing weights along riverbanks and lake shores. All kinds of implements used at annual gatherings were buried and left where they would be used the next year ... at the Sacred Salmon Ceremony at Ti'lomikh or annual berry picking on Huckleberry Mountain or the wocus harvest at Gumbat. Why carry all that heavy stuff on your back? Other artifacts, like rock writings or stone cairns at vision quest sites, mark places of spiritual or mythic significance.

Artifacts were stashed in special places. It wasn't the fault of Indians that white folks rounded them up and dropped them onto reservations, forcing them to leave most everything behind. They had intended to go back!

If one extends the idea of sacred place to the universal native view that "everything and everywhere is alive and has a spirit," then the whole world is a sacred site and should not be recklessly disturbed.

For decades, it was the practice of archaeologists from museums and universities to not only dig up artifacts, but also human bones. There are warehouses and collections bursting with more artifacts than the museums of the world could ever exhibit. There are countless bones that have been waiting a long time to be reburied. It is a belief in many native cultures that the dead cannot find peace with family and ancestors until they are buried properly.

Nothing more needs to be dug up and delivered to museums. Granted, digs over the past century-and-a-half have given us much knowledge, and I am grateful for what I have learned. But that kind of knowledge gives us precious little wisdom. For centuries, cultural wisdom was passed orally through stories. Many of the archaeologists who dig up artifacts and call it knowledge, often dismiss stories as scientifically unreliable. But to native people who know their culture, facts are not wisdom, and it is wisdom that should be gathered, cherished and shared.

People everywhere have a fascination with digging up the past. Since the global coverage of the discovery of King Tut's Tomb, there has been a stream of movies, television shows, magazine articles, and news reports that continue to glorify archaeological digs. From the looting adventures of Indiana Jones to contemporary digs overseen by tribal officials, the dig is not going away anytime soon.

Perhaps we can shift our consciousness into the next level of doing the right thing, for science and for native people. Give all native sites with artifacts the same legal protection we give burials in Oregon. After documenting a dig, return everything to the earth, with a ceremony conducted by elders. As for current Indian exhibits, I would encourage museums to bring in natives to rewrite exhibit labels into stories that dramatize the differences between facts and wisdom.

And lastly, let's empty the warehouses. Let's send each artifact and each bone back home. Not to reservations, miles and miles from original homelands, but back to where they belong.

One arrowhead at a time, reburied in the right place, is a sacred gesture that truly makes a difference.

* * * * *

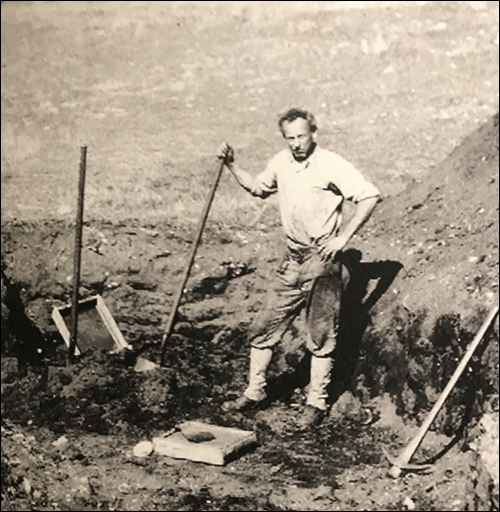

The photos show Chuck Jackson, Dr. John M.H. Kelly, Lower Table Rock, and an amateur archaeologist digging an Indian grave in the 1920s.

Photo Credits | Privacy | Donate

Website © 1997-

by Thomas Doty.